When earlier this spring I wrote that musicians and restaurateurs are two groups that, more than any other, define Louisiana for the world, a friend suggested I also look into our “[visual] art scene and its international impact.” The friend was right about the thriving art scene — but as I looked into that, it led to another potential story, and then others, ranging from art to Katrina recovery to neighborhood revitalization to an industrial controversy and back to food and music.

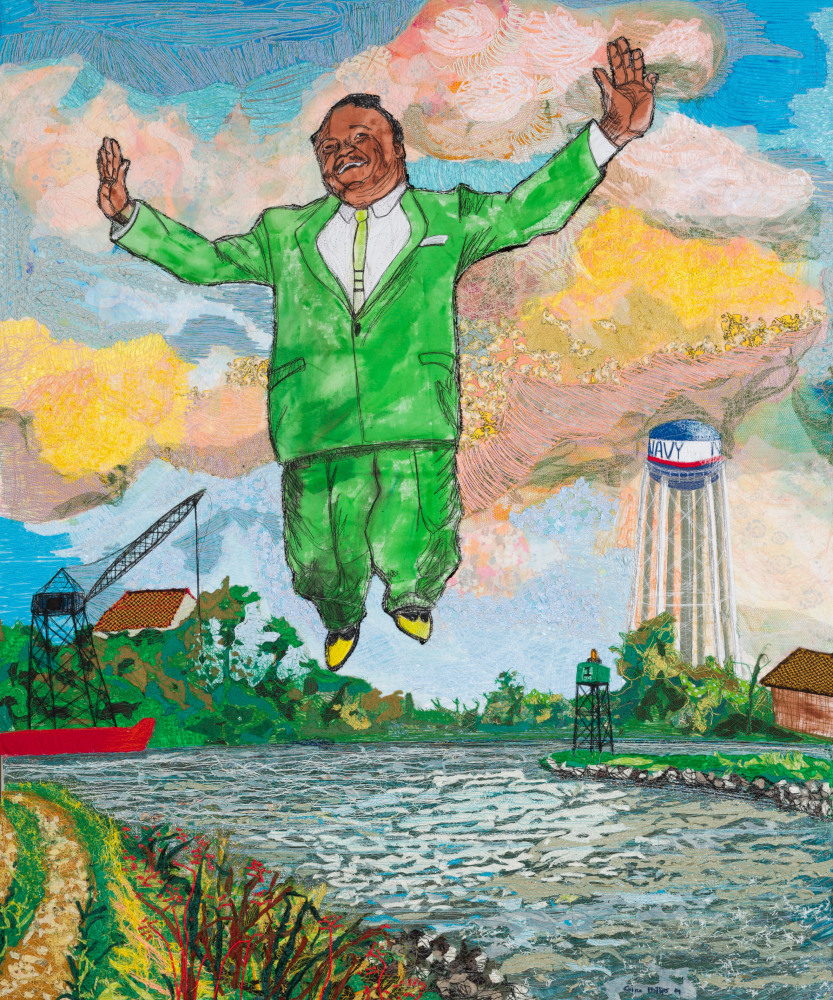

If you imagine what schoolchildren know as “collages” being turned into truly fine art, that might be how laymen would describe Phillips’ colorful productions. Living not far from what was the musician's house, Phillips first gained post-storm acclaim for her Fats Domino Series of fabric paintings.

Domino played a huge role as well in the work of Paul Villinski, who began crafting vinyl butterflies from ruined LP records he found post-Katrina right down the street from Domino’s house. Villinski’s work will be featured at Ferrara Showman in August, concurrent with the Katrina anniversary — and he’ll also do an installation at a New Orleans public school, all part of what Ferrara calls “the ability for visual art to showcase the resilience and transformation of New Orleans.”

That leads back to Phillips: In the very week her new exhibit opened at Ferrara Showman, she featured prominently in a very large story in the London-based Guardian by New Orleans essayist Jason Berry. Berry’s thesis begins with an assertion that the Lower Ninth has become an arts-centered “renaissance district” post-Katrina, with Phillips as one of its guiding lights. That renaissance, Berry posits, is now at risk because of a major grain terminal being built nearby.

Well, the grain terminal is a subject for another day; but when I asked Phillips about Berry’s depiction of a vibrantly artistic community, she agreed but noted that both sides of the Industrial Canal, including the Bywater district opposite her Holy Cross neighborhood, are flourishing.